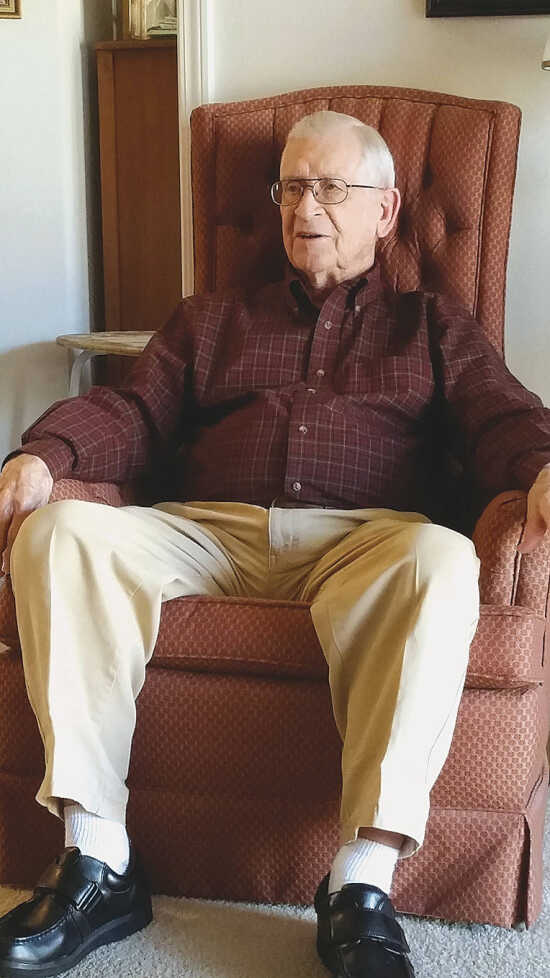

Clarence Whistler read about his own funeral

Editor's Note: See the Saturday Daily Mail for part 2.

Special to the Daily Mail

The Army notified Clarence (Red) Whistler's mother during World War II that he had been killed in action. Red was only 18. Down in his hometown of Belzoni, Miss., they had a memorial service for him. His obituary was published in the newspaper. His mother got bushels of sympathy cards.

A few months later she got a cablegram from Red in Belgium telling her he was OK! He had been freed by the advancing Allied troops.

The cablegram was the only communication she had from him, until some weeks later she was outside their house when she saw him walking toward her. His mother had a bucket in her hand when she saw him. They were never able to find the bucket afterwards!

The following story is a true account of the private adventures of Clarence Whisler, who served in the United States Army from May 1943 through November 1945.

By Clarence H. Whisler

On April Fool's Day in 1943 I was living in Jackson, Miss., with my parents and I went to the draft board and volunteered induction. By May 1 I was summoned to report to Camp Shelby. I passed the tests and after I took the oath to defend my country I found myself dressed and looking like a soldier. I was beginning to learn something about army life such as KP, which started at 4 in the morning and stopped at 11 at night.

In about three weeks I was assigned to Camp Barkeley, Texas, which was the home of the 90th infantry division, but also a medical replacement training center. When we were interviewed and took tests, they asked how many of us could type and about six of us lined up and as they came down the line I listened carefully as to how many words each man claimed to type per minute. Well, I had to announce that I could type 60 words per minute (I really could only type about 40 wpm) and they chose me to go to clerk's school, but still in the medics. I learned how to set up the payroll, fill out supply forms, and type various military forms.

The only field training we received was a 10-mile hike. Another part of our training was called close order drill. I not only learned to do close order drill, but I learned to call it very well. Every morning we had calisthenics before breakfast. On Friday nights we cleaned the barracks. Not only did we sweep and dust, but we washed the floor with soap and then bleach water.

I was very glad to be graduated an Army clerk because the other fellows who didn't get into clerk school ended up as bedpan commandos or medics at the front lines. Another friend of mine, Willis C. R. Washington, became a commando in a hospital.

Being in the medics, we carried no guns so we pulled guard duty with a billet stick. As a result of this I didn't get the regular basic training most fellows did.

One day the sergeant came to me and announced that I was shipping out at 4 a.m. I didn't go to bed. At 3 a.m., the sergeant came in and suggested that we go up to the mess hall and have some cookies and milk to which I readily agreed. When the sergeant offered to carry one of my bags to the end of the company street, I thought, "Maybe the sergeant is human after all." After I loaded on a 2 1/2 ton truck with about 12 other fellows and waved good-bye to the sergeant, a feeling of homesickness came over me.

On the trip we had to change trains several times and one of our group was designated to be in charge. He suggested we look around each town to which we came and catch the next train out. Well, this tactic put us into Camp Phillips, Kan., about two days late, which meant we all were AWOL. They had to call someone to pick us up at the train station.

The 94th Infantry Division was in Camp Phillips in training and now I was to join. After I was interviewed they informed me that there was no need for medical personnel. I was assigned to Company M, 302 infantry battalion. When I arrived in the company area no one was there except the first sergeant. I asked him where the rest of the company was and he said they were out on a problem. When I saw them come in all dirty and grimy I knew this is where I didn't want to be, but I had no choice.

Company M was a heavy weapons company. All the other companies are rifle companies. Heavy weapons consist of .30 caliber water-cooled machine guns and 81 mm mortars.

At this time I was assigned to company headquarters and used as a clerk for the first sergeant. He kept me in the office because I knew all about new forms of records.

I was only here a few weeks when the first sergeant called me aside and said, "Whisler, we are going to your home state for some training, but first we will be on maneuvers in the state of Tennessee for two or three months after which we are assigned to Camp McCain, Miss." I could hardly believe my ears, but it was true.

We loaded on a troop train and the whole 94th Division moved down to Tennessee. Maneuvers are really war games in which one force is the red troop and the other is the blue. We had what was called "problems." A problem could begin at this moment and last 20 to 30 minutes, or it could last for 3 or 4 days or even a week.

When maneuvers were over we moved into camp McCain, Miss. I rode in the back of a jeep, which had no top so I spent most of the time with my head under a blanket. When there were girls along the way the other guys yelled eyes right or left and I came out for a glimpse.

Camp McCain is situated between Grenada and Duck Hill on Highway 51. It is only about 70 miles from my hometown and I now became eligible for my first furlough.

I had planned to sneak in on the folks, but as I approached the house my brother, Roy, came out on the front and after he saw me he made the announcement to the whole family. My mother had remarried after my father died some 13 years before. I now had a half-brother, Jack and a half-sister, Ann. They were glad to see me since I had been gone for more than six months. During my two-week stay my grandmother Young died, but I enjoyed being out of the military for a while.

When I got back to camp McCain everybody had to go through p o e (port of embarkation) requirements, which meant completing various types of training exercises to be eligible to go overseas to a battle area.

The combat ground course required everybody to be on hands and knees with live ammunition and crawling along the course while targets were popped up from various places at which we shot. I really couldn't appreciate the guys on the side throwing lighted firecrackers on us.

I learned how to throw a live hand grenade and fired all the weapons in the company except the 81mm mortar. It takes two men to operate that weapon. My weapon was a carbine. A 25-mile hike was included in p o e training.

On the day we fired the M1 rifle I came back into the orderly room and the first sergeant laughed when he saw my swollen lip. The rifle kicked my lip every time I pulled the trigger. I explained to the sergeant that I couldn't help it. That same day he came in from the firing line, but I didn't say a word about his swollen lip.

That is the way things were for the time we were in camp McCain.

One day we loaded on a troop train and the whole division moved to New York. We disembarked at camp Shanks and stayed there for about a week.

I had a chance to go to New York City to see Times Square and Broadway. Some of our guys were from New York City and they helped the rest of us get downtown on the subway. We got off at 42nd St. and Broadway and just spent the night wandering about looking at all the lights. We went to a theatre and the stage door canteen, but we had to be back in camp by 0600. We were in camp for a couple of days before we shipped out by train, crossed the Hudson River and boarded the Queen Elizabeth.

The whole 94th Infantry Division, plus attached units that numbered about 15,000 men, were loaded on the boat. When we moved out of the harbor I couldn't see the statue of liberty because we were set up in units and each unit was confined to a small space to maintain balance on board the ship.

It took six days and six nights to cross the Atlantic and the only movement made by the ship was changing course to keep the submarines away. We were also fed by unit numbers and when our number was called we went down one deck and went through the chow line. After we ate and washed our mess kit it proved a problem to get up the steps to the top deck because enough grease dripped off so many mess kits the steps were slick. I slept on deck one night and traded off with another soldier to sleep on a hammock the next night.

The Queen Elizabeth dropped anchor off the coast of Scotland and when a man in a rowboat loaded us on for the trip to the harbor we asked him where we were. In his Scottish tone he said, "Glasgow, Scotland." When we reached the shore we were met by the Scottish Red Cross with hot coffee and doughnuts. The Scottish Highlanders were also there with their bagpipes and playing a tune just for us.

We boarded a troop train and moved through Scotland into England. We disembarked close to Malmesbury where a camp was already set up with squad tents and the kitchen was housed in a Quonset. There was nothing to do here but wait until the order was given to move to the southern coast of England to cross the English Channel. The first sergeant was giving out passes to London on a 36-hour basis. One group had already gone on pass and now another group was being formed. The sergeant came to me and said one of the fellows had cancelled out to go later and I could take his place in the group. I accepted.

I never saw streets so crowded as I did in London, but there were troops from all the allied nations. A buddy and I hired a taxi and the driver was very nice. When we drove up to some landmark he got out with us and told what he knew about everything. We saw the houses of parliament, Big Ben, Cleopatra's Needle, Westminster Abbey and the Tower of London. I was impressed to see the things I had only read about in school.

When I approached St. Paul's Cathedral there was a sign on the front steps warning: bomb in basement enter at your own risk. I took it as a challenge and walked right on in and sure enough there was the bomb, which had been dropped through the dome and had not yet exploded. The rest of the cathedral was intact and very impressive to me.

We also went to a British canteen and I paid three and one half pennies for some cookies and coffee. I was amazed at the kind of money they used and how cheap everything seemed to be. The rate of exchange was a 4.25 pound to the dollar, so those pennies were worth more than I thought.

When we arrived back in Malmesbury the order came out that all passes were cancelled and we were to move out to southern England to cross to France. The trip was uneventful as well as the landing on the Utah beachhead compared to the troops who made that trip 94 days ahead of us, but I was content to have it this way.

Our first assignment moved the division down to the western coast of France near two towns, Hennebont and Nostang. We were a holding force for the pocket of German troops who were cut off from their main forces when the invasion came. It was here that I was transferred out of company headquarters to a machine gun squad and I began to learn more about up front and what it means.

One of the first things that had to be done was to dig a garbage sump, which measures six feet by six feet by six feet. Four of us privates were sent out to dig this sump.

We also dug machine gun emplacements all along a line between the aforementioned towns. In one place I had my own hole dug out and structured on a 90-degree angle for the entrance. This way shrapnel wouldn't hit me while I was in there. One day the enemy moved close under the cover of trees and bushes and fired their 88mm gun point blank at us. I was standing in an apple orchard and I don't hear the familiar scream of the shell before it explodes. I hear the explosion and there is no scream. It didn't take me long to get to my dugout.

Our machine gun was set up on a high position overlooking a valley in which we could see a house. We fired several rounds to make sure the bullets were going through the window. Then we loaded our machine gun belt, which holds 250 rounds with one tracer and three incendiary combinations. That night when we knew the Germans were in the house we fired the whole belt, which set the house on fire and gutted it.

The FFE (free French of the interior) were always walking along our line of defense and it sounded like a war going on by the way they were always shooting at something. They brought a whole box of German hand grenades for us to throw which we did. They are commonly called potato masher because of their looks. They also had a German rifle and were shooting wooden bullets. I held the rifle next to a tin can and it never knocked it over. The Germans must have used the bullets for sound effects.

See the Saturday edition of the Daily Mail for Part 2.