Bill Phelps: From Nevada High athlete to political star

Bill Phelps rise to Missouri’s lieutenant governor has small-town roots, with the former multi-sport athlete having graduated from Nevada High School in 1952.

Phelps was elected Missouri’s 40th lieutenant governor in 1972, and re-elected in 1976. Prior to serving in that capacity Phelps, a Republican, cut his teeth in the Missouri House of Representatives in 1960. Representing Kansas City’s Plaza district, Phelps was subsequently re-elected to five terms.

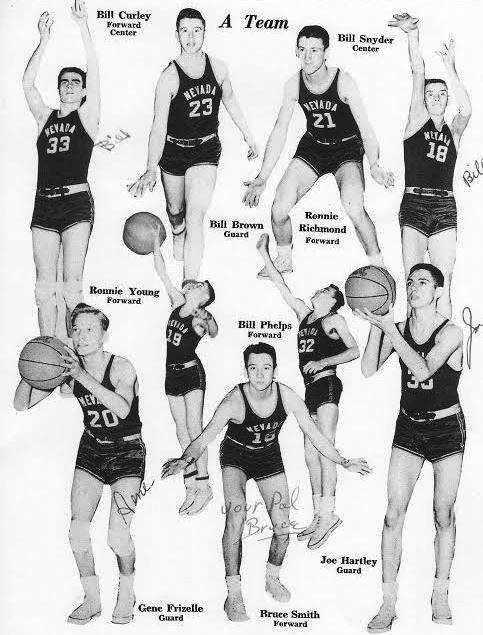

In part one of the story, published by the Daily Mail in early March, Phelps reflected on his days as a Nevada adolescent, specifically the 1950-51 Nevada High School basketball team.

A junior starting small forward, Phelps recalled that Nevada, looking to secure a berth in the state semifinals, led Joplin 36-35 with time winding down in regulation. Phelps came up with a steal and looked to make it a two-possession game with a breakaway lay-in (the three point line was still years away).

“As I was dribbling towards the goal, I was tripped,” Phelps said with a tinge of sadness in his voice. “I fell to the floor and there was no foul called.”

What happened next sealed the Tigers’ fate as Joplin scored a go-ahead lay-in en route to the narrow victory. Nevada had defeated Joplin, the defending state champions, earlier in the season. The Tigers only other loss came against Ozark, as Nevada finished 14-0 in the Big 8 to claim the Conference crown.

“So that was the end of our great season,” Phelps said of the contest that was played at the old Memorial Hall in downtown Joplin. “It was kind of a tough crowd; they were very vocal.”

Phelps added that he was pleased that Nevada was able to exact revenge on Joplin in the 1951-52 season opener.

“We returned the favor,” Phelps said with a chuckle.

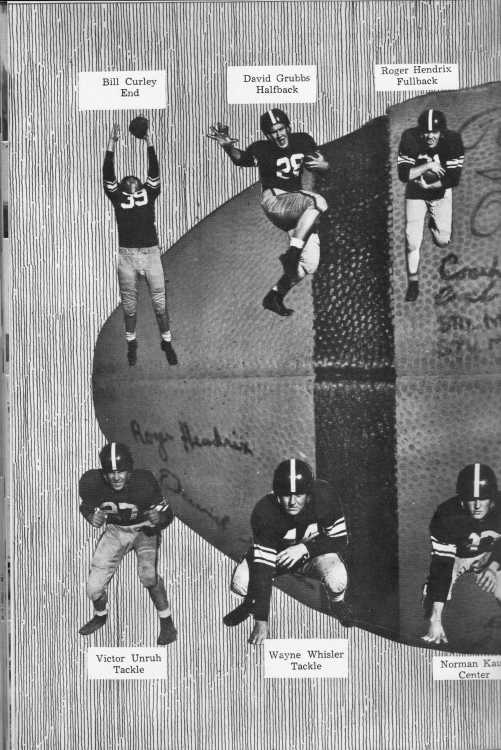

Phelps, an All-American kid, was also Nevada High’s quarterback as a senior in the fall of 1951, playing for legendary coach Gene Rimmer.

He recounted the penultimate game of the ’51 season, a non-conference road contest against Joplin at Junge Field. Late in the fourth quarter Nevada trailed by a touchdown.

Looking to engineer a game-tying drive, Phelps lofted a pass intended for Bill Curley near the Joplin 10-yard line.

“(Curly) got down the field and turned around, and I threw a pass that was right on target,” recollected Phelps.

Phelps tight spiral, however, fell incomplete, dashing the Tigers hopes for an upset victory.

“I thought it was pass interference and Bill did too,” noted Phelps. “The Joplin player interfered with Curley, and once again that referee didn’t call it. That would have been big for a Nevada team to beat Joplin at Junge Field.”

Phelps added that he and Curley had excellent rapport as a quarterback-wide receiver duo in an era know for the “three yards and a cloud of a dust” offense.

“We connected on a lot of passes,” said Phelps. “We had a really good passing attack my senior year. It was Curley and me that were leading the attack. And the games that we won, that was the key — passing.”

Phelps said that current Missouri football juggernaut Webb City was Nevada’s biggest rival.

“They were hard to beat,” he said. “The Webb City head coach’s son was a quarterback, Jimmy Hunter. He went on to play quarterback at Missouri.”

Phelps added that Curley, a two-way player, went on to play linebacker at Missouri.

Upon graduating from Nevada High in 1952, Phelps enrolled at the University of Missouri, where he was recruited by legendary Mizzou football coach Don Faurot.

“He recruited me to play quarterback,” said Phelps. “He had heard from coach Rimmer that I was a good enough passer, and he liked my height. I was around 6-foot-1.”

Phelps said he received a hand-written letter from Faurot, who coached at Mizzou from 1935-42, and again from 1946-56, compiling a record of 101-79-10.

“It was a very nice letter,” said Phelps. “But he said I can’t offer you a football scholarship because your father (Dean Phelps, a Nevada dentist), is able to financially support your school expenses as a professional man.”

Faurot, however, invited Phelps to try-out for the team as a non-scholarship athlete.

“That was a very fine compliment from coach Faurot,” added Phelps.

Phelps said he then tried out for the freshman team.

“In those days, freshman couldn’t play on the varsity team,” said Phelps. “So I went out for freshman football, and decided that I wasn’t fast enough to be a quarterback in their system. So I dropped out of freshman football.”

Phelps said he then pursued basketball at Missouri.

“It so happened that (future Mizzou coach) Norm Stewart and I were in the same class,” said Phelps.

Phelps said that during tryouts his freshman season he committed a cardinal sin during a passing drill run by head coach Wibur “Sparky” Stalcup.

“I did something I had never done before in a game,” Phelps said in a somber tone. “And that was to pass the ball behind my back.”

Stalcup, old-school to the core, wasted no time cutting Phelps for the misdeed.

“He thought that I was a hot dog, but I wasn’t,” said Phelps. “And I was not trying to impress him at all. I don’t know why I did it.”

Phelps said he turned the incident into a positive.

“I consider that as a life-lesson that I learned — that you cannot be something that you’re not,” he said. “It’s a lesson that stayed with me throughout my life.”

Stalcup’s knee-jerk reaction to the razzle-dazzle pass effectively ended Phelps sports career.

“I went on to use my brains instead of my brawn,” quipped Phelps. “I became a student-leader at Missouri, and ended up on the Leadership Honor Roll with Norm Stewart. And we were in one of the top student offices at the University of Missouri.”

“The leadership experience I had as a student leader was helpful for the rest of my career,” said Phelps, who graduated in 1956 with a degree in economics.

Phelps then graduated from the University of Missouri School of Law in 1959. In late 1959 Phelps joined a law firm in Kansas City, Missouri. He had also completed his active duty service with the United States Army after being commissioned by the ROTC as a second lieutenant on graduation day in 1956.

Political career

In 1960 Phelps launched a successful bid for state representative while working for the law firm Morrison, Hecker, Cozad and Curtis.

“I won my first race,” said Phelps. “I was re-elected five times and served six two-year terms in the Missouri House of Representatives.”

Phelps said his successful bid for a seat in the house was boosted by support from the Young Republicans as well as the Kansas City Star.

“I received great support from the Young Republicans,” he said. “We worked precincts in Kansas City and distributed literature throughout neighborhoods.”

Added Phelps: “I had an apartment on the Plaza, and was standing out in front of the apartment building on election day (1960) greeting everybody that came out to vote. And I won, so it was a fun thing.”

With the advent of technology such as cell phones and other forms of electronic and social media, Phelps said elections are vastly different than they were in 1960. Today’s polarizing political climate is often dominated by personal attacks.

“With today’s elections, I don’t like all these personal attacks that are being made on candidates,” lamented Phelps. “It wasn’t like that in our time. We were out competing for votes, but we weren’t tying to destroy the opposition like you’re seeing today.

“People are so desperate to win, and they have more money to spend on advertising than in our day, when money was hard to come by. And as a result, they have the ability to smear the opposition, which you can see from time-to-time in political campaigns today. Otherwise, I think it’s a very competitive system, and I believe in the two-party system.”

Phelps said one of his crowning achievements was his role in shifting Missouri from a Democratic to a Republican state.

“That started in 1968 when Jack Danforth won the Attorney General’s office and Kit Bond won the State Auditor’s office,” said Phelps. “And then four years later, Kit Bond won the Governor’s office, and I won the Lieutenant Governor’s office, and they appointed John Ashcroft the State Auditor.”

Phelps continued: “So from that time period, 1968 to 1972, the Republican Party really came to life and had been revived (in Missouri). The Democratic Party had control of the state from 1932 until ’68, with only one exception, in 1940, after (Democrat) Tom Pendergrast was convicted of income tax evasion and sent to jail. We broke a 40-year hold by the Democrats on the state-wide offices.”

Phelps said one of his most memorable moments as lieutenant governor came in 1976 the day after Bond was defeated in his re-election bid for governor. With Bond out of the state, Phelps held complete authority over constitutional powers.

“(Federal) law enforcement came in and said they had a subpoena for information that I may have had on Richard Rabbitt.”

Rabbitt, a Democrat from St. Louis was Speaker of the Missouri House of Representatives from 1973-76.

“They wanted Richard Rabbitt’s tax returns,” noted Phelps. “As the acting governor, I had the power to authorize the acceptance of the subpoena and order the subpoena be executed. And so the tax returns were released to the authorities.”

“It was a memorable event, because (Rabbitt) was later convicted of bribery and was sent to prison.”

To add insult to injury Rabbitt narrowly lost to Phelps in his bid for lieutenant governor in 1976.

Another big-time moment for Phelps came in 1972 when Richard Milhous Nixon, the 37th President of the United States, visited Kansas City.

In the spring of ’72 Nixon appointed Kansas City police chief L. Patrick Gray as the new acting Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

“At the Federal Building in downtown Kansas City, President Nixon held a little ceremony,” said Phelps. “Bond was out of the state, so I was asked to (take his place) at the ceremony where the Kansas City police chief was appointed director of the FBI. And so I was out there with the president representing the state of Missouri.”

Phelps said he is most proud of a bill he introduced while in the Missouri House of Representative in the early 60s.

“I was in the minority,” said Phelps. “And I sponsored a bill in the house that created a full-time (continuous) grand jury in Jackson County. With all of the history of criminal (activity) in Jackson County, there was only a four-month period (where the grand jury convened).”

Phelps said the bill passed in the house and ultimately senate with bipartisan support, handing him a legislative victory. The bill was adapted into law after being signed by governor John N. Dalton, a conservative democrat — and has remained on the books ever since.

In addition, the University of Missouri system, which includes campuses in Columbia, Kansas City, St. Louis and Rolla was created in 1963 by a bill that Phelps worked hard to pass.

Phelps, 83, currently resides in Houston, Texas with his wife.